Critical Encounters with the Past

*** This is an excerpt of a long interview I did with Paul Guyer in November 2014. The full text, including our discussion of Kant’s aesthetics (which is left out here), is published in the book Conversations on Art and Aesthetics. Please note that this is only a draft. ***

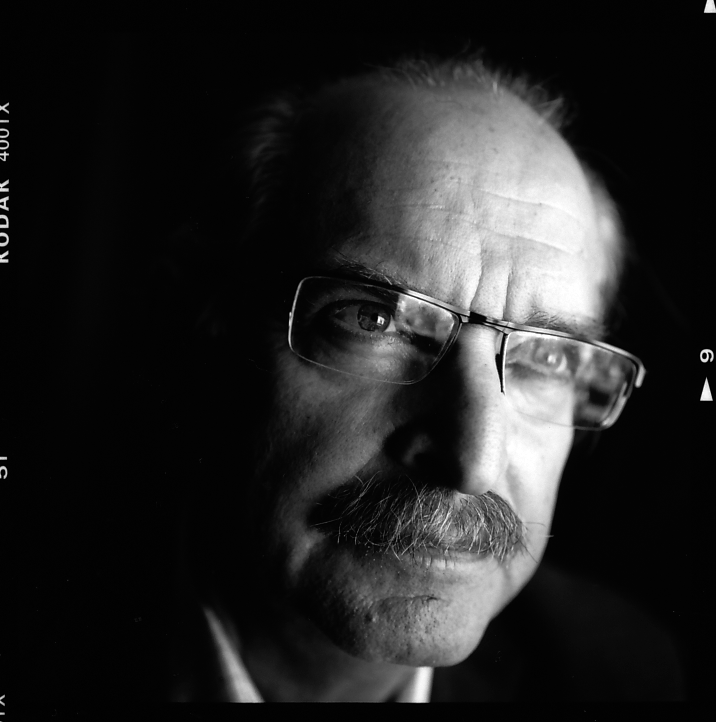

If you want to know more about the history of aesthetics in the modern era, there’s no better person to talk to than Paul Guyer. He literally wrote the book. Or rather, the books. His three-volume History of Modern Aesthetics, a philosophical tour de force covering the period 1709-2007 in just under 2000 pages, was published around the time that we had our interview. It’s no surprise then that the philosophical developments in this historical period will serve as the main backdrop for this conversation. Even less of a surprise, at least for those who are familiar with Guyer’s work, is that one philosopher in particular will be at the heart of our exchange. Guyer devoted most of his professional life to the study of Immanuel Kant’s philosophy and is undoubtedly one of the leading Kant experts in the world, so the opportunity to talk to him in some depth about this giant of 18th century aesthetics was too good to pass up on. Guyer’s very first book, Kant and the Claims of Taste (1979), focused on Kant’s aesthetics and since that time he has published numerous papers, essay collections and edited volumes exploring and explaining how Kant helped to shape our discipline (for more details see the bibliography below). He also co-authored a translation of the immensely influential Critique of the Power of Judgment for the Cambridge Edition of the Works of Immanuel Kant. This is not to say, however, that his expertise is confined to Kant’s aesthetics. He co-authored a translation of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason – the book which was also the focus of his second monograph Kant and the Claims of Knowledge (1987). In recent years he has published extensively on Kant’s practical philosophy as well. Kant on Freedom, Law, and Happiness (2000) focuses on Kant’s moral and political philosophy. Kant’s System of Nature and Freedom (2005) consists of essays on both theoretical and practical philosophy, and Kant (2006) is a synoptic work on all of Kant’s philosophy. A study of Kant’s Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals appeared in 2007. He is currently working on a history of the legacy of Kant’s moral philosophy. It is well-known fact that Kant spent his whole career at the same university (Königsberg). Not so Guyer. He served on the faculty of the University of Pittsburgh (1973-78), the University of Illinois-Chicago (1978-82) and University of Pennsylvania (1982-2012) before taking up a position as Jonathan Nelson Professor of Humanities and Philosophy at Brown University in 2012. It all began, however, at Harvard University where he earned his Master’s and PhD degree, in 1971 and 1974 respectively. Among his teachers was Stanley Cavell and I start our conversation by asking whether and how this philosopher may have influenced his outlook on philosophy.

PG: To this day, people are surprised to learn that I was a student of Cavell, since my scholarly work hardly resembles his distinctive style. I was either too smart or too dumb to try to write like him. But he was nevertheless a great influence on me, even if sometimes I have recognized the affinity between questions I have been interested in and his interests only long after the fact. I first heard Cavell as a freshman at Harvard, in the spring of 1966, in his half of a large humanities course, in which the Wittgensteinian Rogers Albritton taught a semester of ancient philosophy (through Augustine) and then Cavell conducted a much less conventional tour through modern thought, from Luther and King Lear through Samuel Beckett, with stops at more recognizable philosophers such as Locke and Kant along the way. One can get a sense of what that course was like from the philosophy chapters in Cavell’s last major work, The Cities of Words. Remarkably, he introduced us to Kant through Religion within the Boundaries of Mere Reason, a late work and in many ways one of Kant’s most obscure; I don’t know what other students made of it, but I have remained intrigued by the implausibility yet sublimity of Kant’s theory of free will ever since, and Kant’s normative theory of freedom, of freedom itself as our most fundamental value, has been a beacon of my thought ever since. I would go on to do both my senior thesis, on the possibility of knowledge of other minds within Kant’s epistemology, and my doctoral dissertation, on the Critique of the Power of Judgment, under Cavell’s supervision. Like a number of his students afterwards, I was inspired by a few sentences he wrote about Kant’s conception of aesthetic judgment in an early paper, “Aesthetic Problems of Modern Philosophy.”

HM: But Cavell was not a Kant scholar per se.

PG: No. For help with Kant scholarship, I was fortunate to have been able to take or audit courses on Kant with several other wonderful philosophers and scholars, including Robert Nozick, Charles Parsons, Frederick Olafson, and finally Dieter Henrich, who first visited Harvard during my final semester as a graduate student, but not too late to introduce me to treasures such as Kant’s lectures and Nachlaß, or notes and reflections. After Kant studies had been rejuvenated in the 1960s by the works of Peter Strawson and Jonathan Bennett, I was one of the first writers in English, along with my contemporary Karl Ameriks, to make much use of this material since the work of H.J. Paton in the 1930s, and I like to think that, whatever the merits of our interpretations, Karl and I permanently elevated the level of Anglophone Kant studies by making use of the full range of Kantian materials indispensable for Kant interpretation.

HM: You also studied with John Rawls, is that right?

PG: Yes, but only as a graduate student, taking his full-year sequence of courses on moral

and political philosophy and persuading him to let me satisfy the requirements of bothcourses with a single long paper on the relation between Kant’s moral and political philosophy — a subject which has become highly controversial in the last fifteen years or so and on which I have continued to work. Rawls was a gentleman and a scholar, as we used to say, and as the second reader for my dissertation very much encouraged my work on Kant’s aesthetics and its moral implications. But I was not as deeply influenced by him as I was by Cavell or as some of his other students were — their names are too well-known for me to have to mention — and I always somewhat regretted that he backed away from the Kantianism of A Theory of Justice in Political Liberalism. I was also puzzled that Rawls did not make more use of Kant’s actual political philosophy in constructing his own, and find his approach to Kant’s moral philosophy in his Lectures on the History of Moral Philosophy somewhat conventional. But I have only become more convinced over the years that he did divine the core insight of Kant’s practical philosophy as a whole in the famous section 40 of A Theory of Justice, the section on “The Kantian Interpretation,” and continue to find that inspiring.

HM: What exactly were your motivations in studying aesthetics for your PhD?

PG: They were partly professional and partly personal. I took up Kant’s third Critique for my dissertation partly because I had already written on the other two in earlier exercises, and partly because the field was at that time (1971-73) pretty much wide open, and I could get away with saying more or less whatever I wanted! But I was also inspired to study aesthetics by the fact that my father, although he made his living as an advertising art director, was a well-trained and serious painter, and was painting quite intensively and showing his work in New York when I was in college and graduate school. Every time I would come home for vacation he would immediately drag me into his studio, show me his latest work, and ask me what I thought. Well, I liked some and disliked some, but would search for ways to explain why. As a budding philosopher, I thought aesthetics might help me. Of course, the main thing that you learn from a study of the history of aesthetics, in the twentieth century as well as earlier, is that there are all sorts of interesting reasons why people enjoy and value art (and natural phenomena as well), but the one thing that we can never get is determinate principles for the evaluation of particular works. Nevertheless, my father and I did have many interesting conversations over the years — he continued to paint until a week before he died, at almost 96 — and I was particularly pleased when I was able to use images of his work as the cover-art for several of my books.

HM: Has the discipline of aesthetics changed very much since you started as a philosopher?

PG: It certainly has, in ways that I ended up documenting in the twentieth-century volume of my History of Modern Aesthetics. I have to say that my own entry into the field was somewhat orthogonal to what was customary at the time, since, as I suggested, I came it as an incipient Kant scholar, studied eighteenth-century German and British aesthetics as the background for Kant, learned about some strands of twentieth-century aesthetics (e.g., Cassirer and Lukács) in the course of my Kant studies, but didn’t learn any of the standard material until later — Cavell, in spite of his title as “Professor of Aesthetics and General Value Theory,” never offered a standard aesthetics course during my years at Harvard, and, although his own work had begun with papers on American pragmatism, once told me he had given up on pragmatism because it had no sense of tragedy (although years later he didsteer me towards Dewey). But, as I later learned, and what was perhaps the reason why Cavell didn’t teach a standard aesthetics course after his then still recent move from Berkeley to Harvard, in the mid 1960s aesthetics was still very much in what might be called, after a famous article, its “dreariness” phase: the initial impact of Wittgenstein had been very much to narrow down the acceptable topics for aesthetic theory, from its traditional focus on the nature of aesthetic value and experience, to supposedly publicly accessible matters, such as the logic of critical discourse and the definition of art. Even within the “linguistic turn,” there were more interesting discussions — for example, Goodman’s Languages of Art had come out in 1968, the year Goodman finally returned to Harvard, and though he had a reputation as a martinet in the classroom, his work was also taught by the wonderful (and just recently deceased) Israel Scheffler. So I did learn that, although I found it alien because Goodman still insisted that aesthetic theory had nothing to do with pleasure and value. Eventually I learned that there were those who had withstood the temptations of what I call the first wave of Wittgensteinianism, such as the admirable Monroe Beardsley, whose work I came to see as a valuable synthesis of Dewey and Kant; then came the second wave of Wittgensteinians, as I see it more influenced by Part II than by Part I of the Investigations, namely Cavell and Richard Wollheim (although to be sure neither was influenced exclusively by Wittgenstein); and we learned to distinguish Danto’s conception of an “art world” from Dickie’s, Danto’s being more a mental world of theory than Dickie’s external or sociological world, which in turn allowed us to see that there was more wisdom in Collingwood’s Principles of Arts than the apparent extremism of its Book I initially suggests — and then the way was open for aesthetics to reconnect with its rich history, and for a thousand flowers to bloom in the diverse field we have today.

* 18th CENTURY AESTHETICS *

HM: The philosophical discipline of aesthetics not only received its name in the 18th century, when Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten introduced it in his 1735 master’s thesis, but it also really took flight in this period, producing many of the works that we now consider to be absolute milestones in the field. Which societal or intellectual changes do you think triggered and made possible this immense outburst of activity in aesthetics?

PG: There were a lot of factors at work, and in some ways this is more a question for a real historian than for an historian of philosophy! Baumgarten’s work was triggered by a desire to make more space for the role of the senses in the rationalist epistemology of the Leibnizo-Wolffian philosophy, which was itself however a more worldly reaction to the rigors of Pietism that prevailed in Prussian Halle at the start of the eighteenth century (his Pietist opponents had engineered Wolff’s expulsion from the university and banishment from Prussia in 1723, and, hard as this may be for us now to comprehend, Baumgarten initially had to study Wolffian philosophy clandestinely). I mention Pietism because it, like other puritanical protestant movements of the mid- and late seventeenth century, can be thought of as an extreme, iconoclastic reaction to the manipulative use of art in the Counter-Reformation (perhaps the kind of thing Collingwood was still fulminating about two centuries later as “propaganda” rather than “art proper”), and then we can think of the eighteenth century as thinking “Well, we’ve had enough of that”! This anti-anti-aesthetic response probably took place both within circles that continued to take religion very seriously (think of Bach) as well as within both aristocratic and bourgeois circles for whom religion was becoming less important — but who wanted some other justification for their interest in art. The sheer increase in literacy and readership among the more monied and leisured classes of society also probably had something to do with the growth of aesthetics in this period, as the numbers of books published on all sorts of subjects increased exponentially in the eighteenth century — just look at the numbers of titles included in Eighteenth Century Collections On-Line, and that’s only for English titles.

HM: What about Terry Eagleton’s ideological explanation that in the eighteenth century ruling elites saw aesthetic theory as a way to cement their hegemony over other strata of society?

PG: I don’t buy that. First of all, that claim probably gives more power to theory than it almost ever has; and second, I think that if you read writers like Kant, Kames, Schiller and many more with an open mind, you can see that they saw the increasing socio-economic stratification of society as a genuine problem and sincerely looked to shared tastes in “public entertainments,” as Kames calls them, that is, in the fine arts but also in the appreciation of nature, as an area in which social bonds that crossed such boundaries could be developed. Schiller’s insistence that socio-political progress could come only through aesthetic education no doubt went too far, but I think that many writers of this period genuinely thought that shared tastes in art and nature could build community, many of their readers did as well, and that aesthetics flourished at least in part for this reason.

HM: A great number of 18th century philosophers are still read and studied today. Inevitably, however, a far greater number of authors and texts have fallen into obscurity. Do you happen to know of any hidden gems that are just waiting to be rediscovered? Or can we safely ignore those philosophers who have not passed the test of time?

PG: We cannot understand the writers we all still regard as important, such as Hume and Kant, unless we know what they read, what they took for granted or what they reacted against. There are many eighteenth-century writers who have been neglected, at least until very recently, and who still have a great deal to teach us. One is certainly Moses Mendelssohn, whose works on aesthetics from the 1750s and 1760s have been brought back into circulation by Dan Dahlstrom’s 1997 translation. Mendelssohn was an extraordinary human being, who came to Berlin at fourteen educated only in rabbinical and talmudic literature but who by twenty-five had mastered all the main European languages and literatures and was making deeply original contributions to aesthetics. I think that he recognized the complexity of aesthetic experience and the diversity of our possible sources of pleasure in art more fully than Kant ever did.

HM: Who else is there?

PG: Baumgarten and his disciple Georg Friedrich Meier are far more interesting thinkers than Kant’s caricatures of them would ever suggest: although he dismissed them as mere cognitivist “perfectionists,” they recognized the emotional dimension of aesthetic experience more fully than he did. Unfortunately, the English translation of Baumgarten’s little dissertation of 1735 has long been out of print, and there has never been an English translation of his main work of 1750-58 (which was only translated from Latin into German a few years ago), nor have any of Meier’s works ever been translated (except for a little treatise on humor). Johann Georg Sulzer, who compiled an encyclopedia of art and aesthetics in the 1770s that is as massive as Michael Kelly’s Encyclopedia, is another very interesting thinker, but only a tiny sample of his entries have been translated. In France, Jean-Baptiste Du Bos and Charles Batteux were seminal thinkers who influenced all writers of the period, although the former’s work is only available in a facsimile of a 1748 translation and the latter’s chief work is just being translated now (by James Young). In Britain, The Elements of Criticism of Lord Kames remained a textbook in American colleges until the middle of the nineteenth century but then fell off the face of the earth. It was republished by the Liberty Fund in 2005 in an edition by Peter Jones, and is also a great work on the various ways in which art achieves its emotional impact. And there’s more…

HM: David Hume’s essay, “Of the Standard of Taste,” has been dominant in analytic discussions drawing upon 18th century aesthetics. But, as you have pointed out, Hume’s aesthetic theory is in fact broader than that essay alone suggests. What are we missing if we only read that famous essay?

PG: What we’re missing if we read only “Of the Standard of Taste” is any sense of Hume’s actual theory of beauty, as well as much sense of his account of the importance of reaching agreement in matters of taste. The essay employs for its specific purposes a simplistic, what I once called “ingredient” account of beauty, and presupposes that we care about a standard of taste rather than explaining why we do. But throughout the Treatise of Human Nature Hume constantly recurred to aesthetic cases to illustrate his conception of the imagination as well as to illuminate his account of moral sentiments and judgments, and through all those discussions we can learn that he had a far more sophisticated account of aesthetic experience, aesthetic qualities, and aesthetic value than is on display in “Of the Standard of Taste.” Not that there is not much wisdom in that essay: I’ve argued that unlike such contemporaries as Alexander Gerard and James Beattie, Hume did not offer a naïve self-help manual for developing good taste, but recognized that only a few members of any society would have the leisure and resources it would take to become qualified judges — but also that others should care about the judgments of those few because many a person is capable of “relishing a fine stroke” when it is pointed out even if his or her own resources and experience wouldn’t allow the discovery of such aesthetic riches without outside assistance. I think this remains an insightful account of the function of much criticism.

HM: More generally, what would you say is missing from our understanding of aesthetics if we read only Hume and not the other empiricists, or if we read Kant and not any of the other 18th century German philosophers?

PG: I think that if we read either or even both apart from their context we don’t get a full sense of the potential richness and complexity of aesthetic experience. Both were brilliant philosophers, but turned to aesthetics for very specific theoretical reasons, or in support of specific points in their larger philosophical systems, and didn’t give the arts and aesthetic theory as much thought in their own right as did some others for whom art and aesthetics were more central to their intellectual lives.

HM: You mean some of the figures you’ve already mentioned?

PG: Yes, people such as Mendelssohn and Kames — even though both obviously also had other concerns, the former being an important religious thinker and the latter the leading jurist of his country. And then there are thinkers like Adam Smith, for whom (as far as we can tell from what he left), aesthetics was a once-off subject, but who nevertheless had an interesting idea no one else had!

HM: What was this idea?

PG: In a posthumously published essay on “Imitation,” probably intended for a “connected history of the liberal sciences and elegant arts” that he never completed, Smith argued that what we enjoy in imitative art is not the imitation as such (which Plato had long before pointed out can readily be achieved with a mirror), but rather the feat of representation in a medium that does not resemble the represented object, as when we represent a three-dimensional body on a two-dimensional picture plane, or a living, colored body in white marble. This opens up the way to an appreciation of invention and artistry in a way that previous theories of imitation had not. Smith could hardly have foreseen Analytical Cubism, but his idea explains its fascination.

(…)

* For the remainder of our conversation, including a discussion of Kant’s aesthetics and a series of thoughts on the philosophy of art from the 19th century to the present day, please see my forthcoming book Conversations on Art and Aesthetics (Oxford University Press, 2016). *