The Emotions in Art

** What follows is only a brief excerpt. The full text is available in Conversations on Art and Aesthetics (Oxford University Press, 2017). **

In contemporary emotion theory there is wide agreement on the fact that emotions cannot simply be identified with feelings or judgments. A person can make the right kind of judgment, say, that there’s a dangerous animal right in front of her, and yet fail to be in the corresponding emotional state of fear. Likewise, one can have certain feelings that are not emotions – think of hunger pangs or sexual urges. So, an alternative and more subtle account is needed, which is precisely what Jenefer Robinson delivers in her landmark book, Deeper than Reason (2005). Robinson believes that emotions should be thought of as complex processes in which a non-cognitive ‘affective appraisal,’ which is fast and automatic, causes subsequent physiological responses, motor changes, action tendencies, and changes in facial and vocal expression. The function of the affective appraisals is to draw attention immediately and insistently by bodily means to whatever in the environment is of vital importance to the agent (This is nauseating! in the case of disgust; or This is dangerous! in the case of fear). These primitive appraisals go on to produce physiological states that ready the agent for appropriate action and signal to others the agent’s state. This may then be followed by a more discriminating cognitive appraisal or monitoring which kicks in to see if the affective appraisal is appropriate and, if necessary, modify automatic activity and expression. Finally, when all the requisite appraisals have been made, the agent may try to classify the state he or she is in by using one of the familiar emotion terms. However, as Robinson is careful to point out, many such after-the-fact assessments are prone to error. Furthermore, different languages carve up the territory in different ways and since no language has the resources to name all subtle emotions, it is very likely that many emotions remain nameless. In any case, at the root of the emotional process, and indispensable for it, is a rough-and-ready, quick-and-dirty affective appraisal. Such ‘non-cognitive appraisals,’ Robinson thinks, are the reason why we experience emotions as passive phenomena, because once an affective appraisal occurs the response occurs too. That is why we never feel fully in control of our emotions and why emotions remain in important ways immune to assessment as rational or irrational. Hence also the title of Robinson’s book, Deeper than Reason – a deliberate nod to Edith Wharton’s novel The Reef where in a crucial and striking passage one of the characters ‘felt a warning tremor as she spoke, as though some instinct deeper than reason surged up in defense of its treasure.’

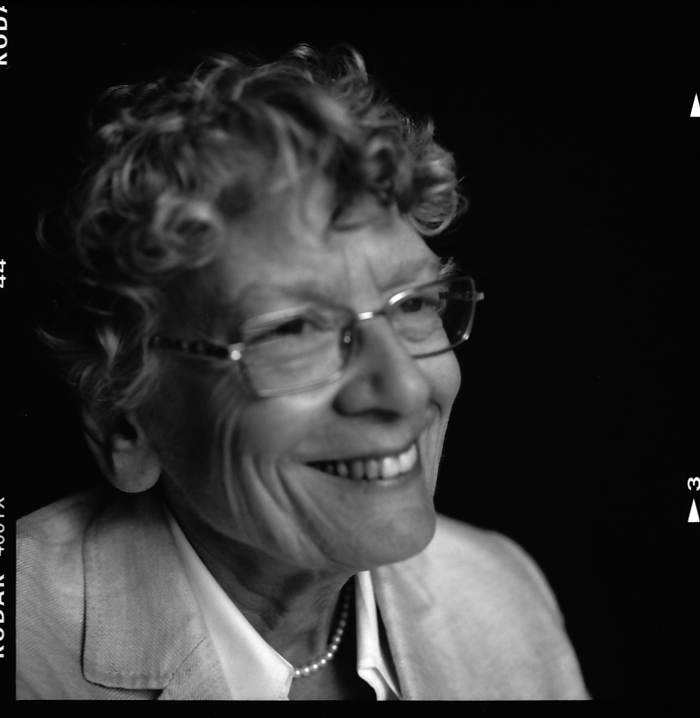

Wharton’s novel is by no means the only work of literature that is discussed at length in Deeper than Reason. Multiple pages are devoted to Keats’s Ode to a Nightingale, Matthew Arnold’s Dover Beach, Shakespeare’s Sonnet 73 and Macbeth, Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, and Henry James’s The Ambassadors. Add to this occasional references to George Eliot, T.S. Eliot, Thomas Hardy, Ernest Hemingway, Franz Kafka, P.B. Shelley, and you know you are dealing with an author who has a genuine and longstanding passion for literature. Indeed, early on in my conversation with Robinson I learn that she studied English Literature as an undergraduate at the University of Sussex and even considered doing a PhD in this field. The reason she decided against this plan is telling: ‘I thought, in my youthful idealistic way, that if you wrote a dissertation on any great work of English literature, you would end up finding it tedious and the magic of this great work for you would be destroyed.’ Philosophy posed less of a risk in this respect. In fact it was partly because she found philosophy so challenging and difficult that she chose this discipline for her postgraduate career. She relocated to Toronto and initially did philosophy of language there. But under the aegis of Francis Sparshott she moved on to philosophy of art and eventually became Professor of Philosophy at the University of Cincinnati, with aesthetics and emotion theory as her main areas of research.

Her years as an English student have certainly been formative ones. For instance, when I ask her about the main influences on her work, one of the first books she mentions is F.R. Leavis’ The Great Tradition: ‘Leavis’s putting those particular novels together as a group – Henry James, Jane Austen, George Eliot, Joseph Conrad – must have registered with me. That great tradition of morally serious, realistic works, where moral values are exemplified by the plot and the characters, and everything is tightly knit together, those are the works I still write about and am most fond of.’ But literature is not the only art form that figures prominently in Deeper than Reason. Robinson discusses paintings by Eugène Delacroix and Caspar David Friedrich and Rodin’s sculpture Burghers of Calais, and she devotes more than a quarter of the book to music, with extended discussions of Shostakovich, Schubert, and Brahms.

All of this fits with the book’s ambition to not just develop a plausible theory of emotion, but also, and more importantly even, to bring that theory to bear on questions about our emotional involvement with the arts in general. Such questions will be central in our conversation. But before we address the role of emotion in art I prompt her to say a bit more about her general theory of emotion and the philosophical context from which it emerged.

Hans Maes: Everything you’ve written on emotion theory begins by a critique of the views of Robert Solomon. That’s what you say in the introduction to your book. Why was Solomon in particular such a powerful trigger?

Jenefer Robinson: Because he’s so obviously wrong! He leaves the emotionality out of emotion. Especially in his early work he defends the view that emotions are judgments. That always sounded so cerebral. And it was completely at odds with what psychologists studied when they studied emotion at that time.

Hans Maes: Solomon came to the topic of emotion, not so much through psychology, but through existential philosophy. Is that something that you’ve engaged with?

Jenefer Robinson: I read the existentialists at the age when most people read them, when I was an undergrad. But I’ve never really engaged with Existentialism since I became a professional philosopher.

Hans Maes: Is that because you see Continental philosophy as incompatible with the analytic style of philosophy that you favor?

Jenefer Robinson: Well, I don’t disapprove on principle of Continental philosophy or anything like that. In fact I’ve tried in various ways to make use of ideas from Continental philosophy. Over the years I’ve taught many classes in literary theory with various friends from English Lit. and Romance Languages, and many of the people in those departments have been influenced by French Structuralism and Post-Structuralism, which come out of the Continental philosophical tradition. In fact, I think the reader-response view of interpretation that I advocate in the book owes a lot to my friends in literature.

Richard Wollheim asked me once to write a brief history of modern aesthetics for the Grove Dictionary of Art. I was very ignorant about the history of philosophy at the time (and I still do have large gaps in my knowledge). But anyway I spent two years learning the history of modern aesthetics. I had to read Hegel and Heidegger and a lot of other stuff then, of course. But I didn’t read the whole of Hegel. Just bits. And bits of Heidegger. So I guess I’ve only dabbled in Continental philosophy.

Hans Maes: Speaking of the history of philosophy, Robert Pasnau of Colorado University wrote an open letter to prospective Ph.D. students in philosophy encouraging them not to neglect the history of their discipline. Here’s a quote: ‘Most of the interesting, important work in philosophy is not being done right now, at this precise instant in time, but lies more or less hidden in the past, waiting to be uncovered. Philosophers who limit themselves to the present restrict their horizons to whatever happens to be the latest fashion, and deprive themselves of a vast sea of conceptual resources.’ What do you think about that?

Jenefer Robinson: I have a qualified view about it. In a way I’m sympathetic to what he’s saying because he’s treating philosophy as part of the humanities, not as a science, which is how a lot of people want to think of it. Can philosophy benefit from an examination of the history of ideas? Sure. But philosophy isn’t just the history of ideas. The way I do philosophy, which is to analyze concepts, but also to take into account whatever is known empirically about the subject that one is dealing with, is perhaps fashionable now, but I think it also has lasting value. If there’s relevant scientific research, then you should use it when you’re doing philosophy. That’s a different perspective from simply thinking that philosophy is the history of ideas.

Suppose you’re reading Descartes on the emotions. You need to know that his science is totally wrong. There aren’t animal spirits, and there isn’t a place where the body and the soul meet in the pineal gland. But, if you look at the concepts he’s working with, at his theory of what emotion is, it still makes a lot of sense. It’s not very far away from William James. So if you’re looking in the history of philosophy for sophisticated analysis of concepts, that’s absolutely a useful thing to do, and it’s also fascinating to see how the analysis of a concept changes over time. And of course the history of philosophy is full of smart guys. Ignore Aristotle at your peril!

Hans Maes: You mention how it is now fashionable in philosophy to engage seriously with the latest science. That wasn’t the case when you started out?

Jenefer Robinson: I think I was early doing it in relation to emotion theory. Lots of people do it nowadays. But I may have been part of the vanguard there. For example my paper on the startle mechanism used a lot of scientific results and it came out in 1995. In fact I remember someone commenting on how unusual it was at that time for the Journal of Philosophy to publish a paper with so much empirical evidence in it.

Hans Maes: But can philosophy really develop in tandem with science? Pasnau, again, argues that philosophy, unlike science and math, does not develop in a steady linear fashion. In fact, he thinks it’s not unlikely that the best historical era in philosophy came at the very start.

Jenefer Robinson: If you look all the way back to the beginnings of philosophy, when some people were supposedly saying that all is water, well, we’ve definitely made an advance on that! (laughs) And is it true of science that it moves forward in a linear fashion? Isn’t that a bit naïve? Anyway, I think there is progress in philosophy in so far as you can get the scientific details right or wrong, say, if you’re interested in something like the mind or neuroscience. I do find it a little irritating when very, very clever people devote themselves to a priori theorizing about the mind, or about what must be the case about consciousness. I feel like saying, ‘Just wait 25 years, you’ll know a whole lot more about the facts.’ The cleverest minds often devote themselves to problems that might be more readily solvable in the future, when more of the relevant empirical facts have been unearthed.

A THEORY OF EMOTIONS

Hans Maes: In taking the science of emotion seriously you’ve arrived at what some have called a non-cognitivist view of emotion. Is that a label you are happy with?

Jenefer Robinson: Certainly in the startle paper I formulated my views in very non-cognitive terms. I emphasized that an emotion is a bodily reaction which somehow or other alerts an animal (or a person) to the presence of something important in the environment. I was keen to maintain that you can have an emotion without any cognition at all. In the late 70s and early 80s, that was thought to be slightly crazy, especially in light of views like Solomon’s or William Lyons’s. Lyons, for instance, claimed that at the root of each emotion there had to be some kind of cognitive evaluation. He called his theory the ‘cognitive-evaluative’ theory. So, the idea that you could have an emotion that was completely non-cognitive, an instinctual reaction, was hard for people to accept. It was an idea promoted by the psychologist Bob Zajonc who studied primitive emotional reactions. Nowadays it’s commonly agreed that there are emotions that are non-cognitive in the sense that they are instinctive reactions to some stimulus that we are pre-programmed to respond to and that can also be observed in lower animals. So then the question becomes: what’s the relationship between those phenomena and more cognitively complex emotions that humans seem to have all the time, like for example, resignation at the thought that one will never be as successful as one’s father, an emotion which presumably rats can’t have.

Hans Maes: How do you answer that question?

Jenefer Robinson: In the 1995 paper I simply said that our bodies alert us to dangers, offences, and losses in our environment, but without explaining how that could happen. In the book I try to give an explanation in terms of what I call ‘non-cognitive appraisals,’ meta-appraisals of a very simple kind such as BAD or GOOD. Or THIS SATISFIES (or FAILS TO SATISFY) My GOALS, or possibly ‘THIS IS A THREAT’ OR ‘THIS IS A LOSS’ or whatever. I was agnostic about the correct way to specify these appraisals. But the idea was that even simple animals can make them and that human beings retain the propensity to make them, even though in human beings there can be a lot of cognitive activity prior to the ‘non-cognitive appraisal.’ So the fish senses a predator – it sees a predator fish approaching or it feels a large displacement of water nearby – and it moves away very fast from what is instinctively registered as a threat. Its physiology is directly affected by the instinctive ‘appraisal’ of threat. In the human case, I may infer that my boss is working up to an angry explosion which will pose a threat to my well-being, because of what he’s saying and because he’s starting to turn red around the ears, which he always does when he gets really angry. Nevertheless what sets off my fearful emotional response – physiological changes, action tendencies, and so on – is a simple meta-appraisal ‘THIS IS BAD’ or ‘THIS IS A THREAT,’ much like the fish.

Hans Maes: So, there’s no fundamental difference between the emotional response of a human being and that of a fish. Some will find that hard to believe.

Jenefer Robinson: Well, it’s not as crazy as all that. What I said in the book was that an emotion episode like this one is always a process, in which there may or may not be beliefs or judgments but in which there is always a ‘non-cognitive appraisal’ that directly causes bodily changes. There can be lots of cognitive activity beforehand as I figure out my boss’s state of mind, for example, and lots of cognitive activity afterwards when I monitor what’s occurred and label my experience or perhaps try to control or modify my response.

(…)